Ants, arsenic, and a spoonful of sugar

by Ellen Airhart

I was knee deep in blackberry roots when I came across the faded green glass bottle, labeled “Antrol Ant Killer” and looking like an old-timey medicine container. Soon I would learn what was inside: arsenic and a spoonful of sugar.

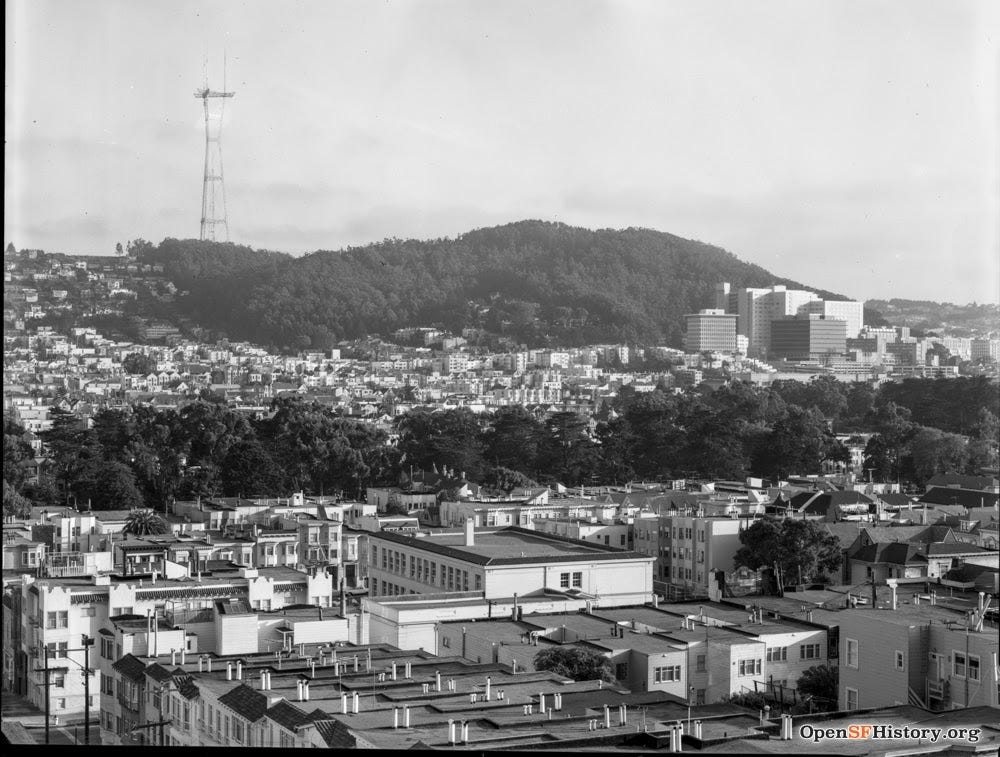

The poisonous artifact was decidedly out-of-place on Mount Sutro, a protected greenspace and eucalyptus cloud forest owned by the University of California, San Francisco.

Arsenic, famously, is toxic. In low doses, it can cause skin, digestive and nerve issues. In higher doses, it’s carcinogenic and lethal. It’s also one of the oldest pesticides in existence.

Throughout history, humans have used it against various enemies, including plague-toting rats. In the early 20th century, arsenic compounds were the most popular pesticide in the United States, fully endorsed by the federal government.

When it comes to ants, sugar and arsenic are a fairly effective poison. “They’re a sweet-loving species,” as well as social creatures, says Vernard Lewis, a retired UC Berkeley entomologist. The communal insects will carry the solution back to their nests and share it with their colony, maximizing its lethality. Once ingested, Lewis said, “Yes, arsenic mixed with sugar and water will kill ants.”

Largely because of the health threats it poses to humans, American insecticide manufacturers stopped making arsenic in 1985 (though other countries, such as China and Morocco, still produce it).

The green bottle of Antrol Ant Syrup I discovered on Mount Sutro, then, appeared to be a relic of a bygone era of insecticides. Its maker, one Boyle-Midway Inc. — producer of home cleaning agents such as Woolite cold-water washing liquid and Easy-Off oven cleaner — formed in the 1930s. Sometime between then and the turn of the new millennium, when official protections were put in place for the greenspace, somebody deployed and abandoned the now-out-of-favor poison.

The same thing, apparently, happened in Muir Woods National Monument, a dedicated park since 1908 and one of the country’s most famous natural wonders. Brian Fisher, curator of entomology at the California Academy of Sciences, who found an almost identical bottle near the monument in recent years. “I found it strange that someone would use Ant Killer in the redwoods,” he says. “There are no ants in the redwoods.”

Trying to kill ants is a mostly pointless exercise.

For starters, there’s too many of them – some 100 trillion or 10,000 trillion on the planet, depending on which estimate you consult. Despite each ant weighing mere milligrams, they take up 25 percent of the earth’s tropical biomass and 15 to 20 percent of its terrestrial animal biomass. Humanity, in comparison, represents about .01 percent of the planet’s total biomass and about 3 percent of its animal biomass.

Certain species have also come to dominate urban spaces. Since Argentine ants hitchhiked to California in 1907 on ships and trains, it’s formed one, state-spanning megacolony more than 500 miles long. They don’t bite humans, but they eat nearly everything (including more than 100 ant species native to California and important to local ecosystems, like the velvety tree ant and the pyramid ant). Argentine ants also have the annoying and economically taxing habit of protecting agricultural pests like mealybugs and aphids in return for the sugary liquid they produce.

Lewis, the retired Berkeley entomologist, used to battle Argentine ants that invaded his lab experiments and wreaked havoc on his collections of oak worms, termite, and other insects. Argentine ants are also a known nuisance in the Bay Area, including Mount Sutro. “It’s a complete nightmare,” says Morgan Vaisset-Fauvel, the program manager for grounds and pest control at UCSF. “There are Argentine ants all over America.”

Lewis thinks it’s possible a land manager might have left the arsenic long ago to target Argentine ants and protect picnickers and local birds and bugs. Vaisset-Fauvel thinks this explanation is unlikely. “Protecting the birds,” he says, is “kind of a very new thing.”

Decades ago, total annihilation was a common strategy for pest control, despite the potentially dangerous consequences.

Arsenic, for example, can leach into the soil, where, in turn, it’s taken up by plants. The historic widespread use of arsenic pesticides in the U.S. means that some foods like rice and apple juice still contain higher-than-normal arsenic levels. In the southern central U.S., for example, cotton farmers dumped millions of pounds of arsenic compounds to destroy destructive boll weevils; about a hundred years later, rice grown there has about 1.8 times the amount of arsenic as rice from California, where arsenic pesticides were used more sparingly.

Today, exterminators instead employ the strategy of creating environments where pests will struggle to survive. Instead of spraying down a house infested by insects or rodents with dangerous chemicals and poisons, pest managers ask homeowners to patch holes and clean up more regularly.

Above all: they avoid the overuse of poisons, which can have consequences that far outlast the life of any pest. These days, no one uses herbicides or pesticides on Mount Sutro. The volunteers remove the invasive blackberries and ivy by hand (with the occasional help of goats). “We're really trying to stay away from any type of chemical as much as possible,” says Vaisset-Fauvel.

When the Ohlone tribe lived in the Bay Area, the land now designated Mount Sutro was a tree-less sand dune with native sage and other coastal shrubs and grasses.

In 1879, former San Francisco mayor Adolph Sutro – an engineer who made his fortune buying up land and prospecting it for precious minerals – bought the land. On arbor day in 1886, he planted mostly non-native blue gum eucalyptus trees with the intention of using them as timber and railroad ties. Turns out, eucalyptus wood grown in the area is brittle and splintery, good only as firewood.

After a fire in 1934, Sutro’s timber operation shut down, leaving no one to tend the area. The forest grew denser, and native coastal shrubs and grasses struggled to thrive in the eucalyptus canopy’s shade. Vaisset-Fauvel thinks that this might have been when the invasive blackberry and ivy started taking over. “Nothing was done at all at Mount Sutro until 2008, when we had the new management plan,” he says. “I think that’s actually where we lost a lot of plants and insects and habitat.”

When UCSF bought 90 acres of Mount Sutro in 1953, it dedicated two-thirds of it as protected forestland and promised to keep it free of unnecessary construction. But two years later, in 1955, the military set up camp near the school’s sanctuary. The area was devoted to Project Nike, which developed anti-aircraft missile systems, as a base for radar and scanning for enemy planes. I walk past the last remaining military structure, a police guard building, whenever I go to volunteer.

In 2018, the school published a 2,000-page report outlining its future plans for the Mount Sutro reserve. Even after many community outreach meetings, there’s plenty of resistance from activists like those that run the website “Save Mount Sutro Forest,” who believe the plan is actually a means to clear the way for development on the property. In the report, UCSF lays out its intention to replace older, unhealthy eucalyptus trees — which have become a fire hazard — with native trees like oaks and laurels.

Under the proposed management plan, they would also replace some of the woodland’s blackberry and ivy understory with native plants, like miner’s lettuce and pink honeysuckle. That’s the habitat restoration work I was doing when I found the green arsenic bottle.

Vaisset-Fauvel thinks that my bottle was left from an overly zealous ant killer at the Nike radar site, or by a dumper from the old neighborhood surrounding the park. He frequently finds old bottles and bits of pipe on what is now called Nike road. He’s even come upon a demolished manhole and live electrical wire. “It’s not like the military left us a blueprint of what was there,” he says, so “there’s always some surprise.”

What is happening on Mount Sutro, to me, is an act of faith. Native coastal shrubs and grasses now grow among remaining roads from the Nike site and sunnier paths created by volunteers. The Sutro Stewards, a San Francisco parks alliance organization, cultivate native species to be planted where blackberry brambles and ivy have been cleared.

These days, city joggers, mountain bikers and volunteers enjoy a space that feels primeval — hopefully not so different from the ancient redwood forests a few miles away. Above them are Australian eucalyptus trees, imported 130 years ago for profit. Below them, members of an Argentine ant megacolony and post-natural exhibits of San Francisco’s human history. If they were to stick their hands in the soil — as I do to dig up and weed out stubborn blackberry roots — they might nudge traces of a decades-old poison that will linger underfoot for the next 9,000 years.

TIP JAR💰

Loved this issue of We’ll Have To Pass? Then send the author, Ellen Airhart, $5 directly on Venmo @Eairhart. To support her other amazing work, follow her on Twitter @EllenAirhart.

This issue of We’ll Have to Pass was edited by Eleanor Cummins and Marion Renault. Our logo design is by Mariana Pelaez.

For just $5/month, you can help us publish incredible stories that otherwise may never have existed.