The first thing you notice when you finish the crossing, the thing you don’t expect, is the quiet. You just sailed across an ocean — a vast expanse of never-ending, constantly changing blue — and spent weeks in constant motion. The stillness that accompanies dropping the anchor, or latching onto a mooring ball with your boat hook, or tossing your dock lines to a marina slip, is expected. And welcome. But the respite from snapping sails, clanking hardware, hull-pounding waves and the ever-present creaks and sighs of flexing plexiglass, wood or steel bring you utter relief. You didn’t know how much you missed the quiet until it’s wrapped around you.

The quiet, the stillness, the relief — it’s all accompanied by a wave of emotion, a feeling of joy and release. You made it. You spent weeks at sea cut, off from home and the world at large, but you sailed across an ocean. You accomplished something momentous.

As it all sinks in, as you pop open that long treasured bottle of Champagne, or beer, or maybe just a swig of rum from the bottle stashed in the bilge for occasions like this, you may also power up your cell phone, connecting to a signal that, for those weeks at sea, felt like a distant, hazy memory. You call loved ones, laughing and crying as you hear their voices for the first time in what feels like forever. Your notifications blow up — emails, texts, Tweets, DMs, maybe all at once, maybe in fits and bursts — and that outside world starts to hit you. Suddenly, your hard-won quietude is engulfed in a different kind of noise.

But what if, in those weeks at sea, that stretch of time that seems to warp as the sun rises and sets and days lose their meaning as benchmarks— what if, as you cruised through that endless expanse of blue, the world as you knew it changed unalterably, and shut down around you?

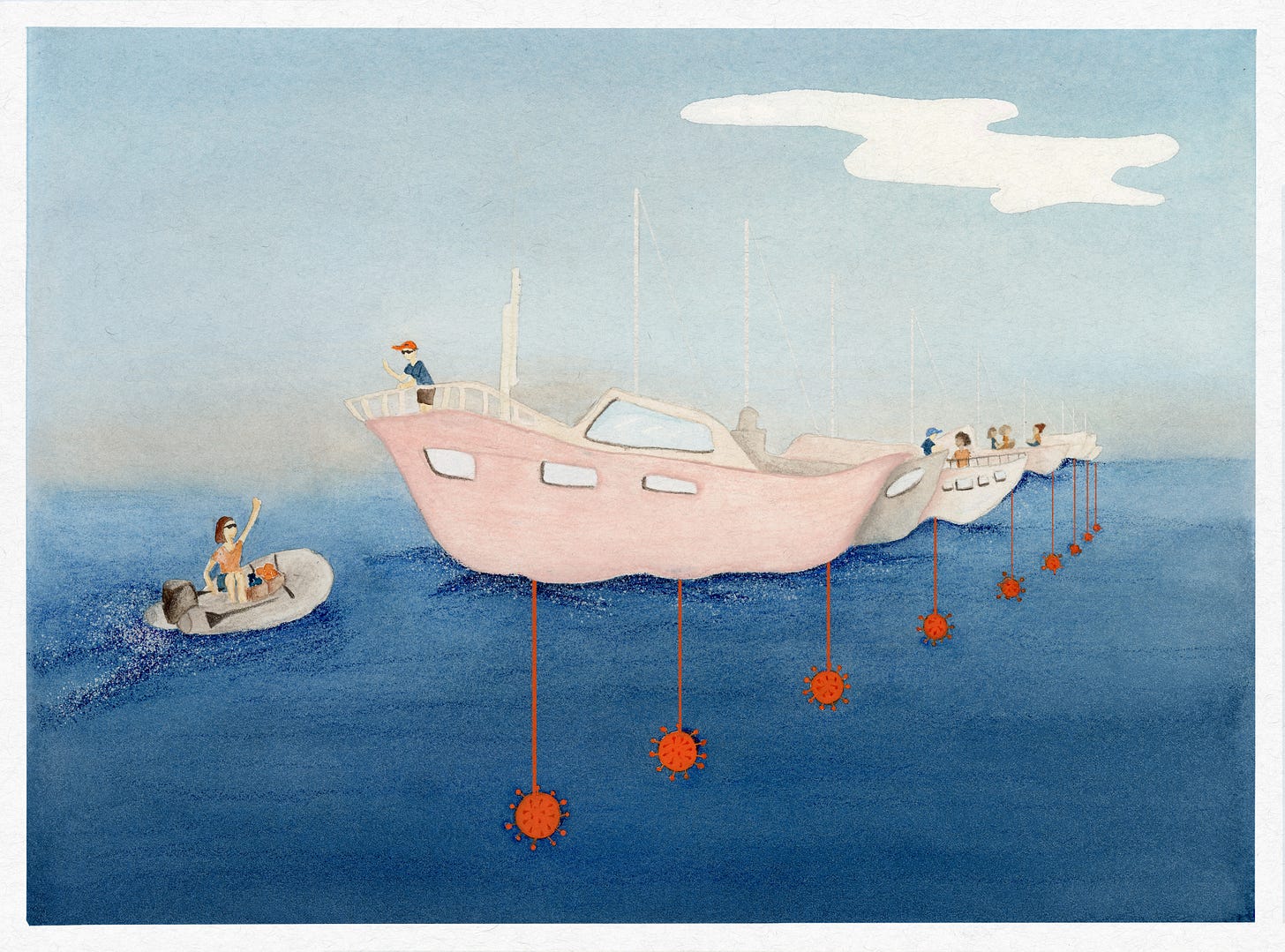

It’s an almost unfathomable study in contrast that sailors crossing the Pacific Ocean experienced this spring as COVID-19 ravaged the world. The reality to which they arrived was unrecognizable from the one they left. And the hallmarks of the sailing lifestyle — freedom of movement, ability to travel where you please, the chance to explore places that most people only dream of — were quickly snuffed out as restrictions tightened around them. What’s more, as inter-island travel was banned, flights grounded, and trips to land discouraged, captains and crew alike began to wonder: What options do we have? Will we, at some point, be able to sail on? And when we can, will we be welcome when we arrive?

The Pacific crossing, a minimum 3,000-mile jump, is the offshore sailor’s dream. At least, it’s certainly mine: I’ve sailed across the Atlantic, island-hopped around Indonesia, and spent ample time zipping around the San Francisco Bay where I live. But the Pacific gets you to the places you want to go — the places that make boat life, and all its ups and downs, unbeatable. The five archipelagos of French Polynesia, hundreds of islands spread across more than a thousand miles of ocean — the lush, volcanic peaks peaks of the Marquesas, the white sand and crushed coral beaches of the Tuamotus, the postcard-famous Society Islands, including Bora Bora, Moorea, and the island of Tahiti, not to the mention the islands of Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa beyond — are the stuff of tropical fantasy, with a rich, ancient local culture to boot. Due to their relative inaccessibility, they’re largely spared the crowded party scene of the Caribbean.

“The whole central group of islands out here, between the Marquesas and Papua New Guinea, is just a sailor’s paradise,” said Andy Turpin, the founder and coordinator of the Pacific Puddle Jump Rally and the chairman of the South Pacific Cruising Network. Turpin, 66, and I spoke in late April, when he was confined aboard Little Wing, his 42-foot ketch-rigged Cross Trimaran, at anchor in the Taiohae harbor in Nuku Hiva. “It’s dynamite! One of the most beautiful places you can actually sail.”

The sailing itself is excellent, too, especially during the right season. From January to late May, with prime conditions in March and April, southeasterly trade winds in the South Pacific turn on, so to speak, as the earth’s rotation tugs at hot air gathered at the equator. Coupled with the tail end of cyclone season in the southern oceans, spring’s optimal cruising conditions keep French Polynesia a sought-after destination for sailors heading west from the Americas.

Which is why, come January and February, boats begin preparing in earnest to cross from Mexico, Panama, or the Galapagos. More and more do so each year. In 2018, 678 sailboats entered French Polynesia, versus fewer than 500 sailboats in 2010, according to Stéphanie Betz of the South Pacific Sailing Network. In 2019, an estimated 1000 boats entered, according to Olivier Meurzec of the Association des Voiliers en Polynésie (AVP), or The French Polynesia Cruising Association.

Numbers aside, sailors reside in the margins of the islands’ ecosystems in many respects. They’ve made the choice to give up things like space, privacy, and potentially, regular showers, to have the freedom to go where they choose, when they choose. They are hugely independent — well-versed at making any situation work, jury rigging everything, and taking care of themselves and their crew. But their presence still has an impact on the place they drop anchor. Some of the best experiences come from making connections on land — to the shopkeepers from whom they’re buying groceries, the fisherman with whom they might trade a bottle of rum for piles of mangos and bananas, the kids who will run up to the scraggly-haired, smiling strangers, giggling and making faces and asking, “Where are you from?”

Striking the balance between the two— the desire to follow your own compass while maintaining respect for the people and places you visit — is paramount for the longevity of ocean cruising. This is, perhaps, even more crucial in the South Pacific, where far-flung islands, many with small populations and extremely limited resources, are at risk of being overwhelmed.

Much of the initial response to COVID-19 was in response to this exact fear: That the more isolated islands would be impacted by a virus to which they had no recourse. Boats were initially redirected to Nuku Hiva, which has the largest settlement in the Marquesas. Later, they were compelled to leave the archipelago altogether. Sailors who arrived after the March 21 cutoff were allowed to stop briefly for provisions and repairs, but were otherwise told to depart as soon as possible for Tahiti or, preferably, to sail to Hawaii. The passage to Hawaii from Nuku Hiva, a 2,000 due north reach—a consistent wind hitting one side of the boat—isn’t a bad sail that time of year. But either scenario is a tough blow after a lengthy crossing.

This has been an issue facing sailors worldwide in 2020. Accounts of changing restrictions from countries around the world and firsthand accounts of sailors grappling with increasingly difficult decisions dominated Noonsite, a go-to resource for sailors seeking real time information about ports of entry, paperwork, sailing conditions, and more. The Pacific islands initially were spared a major outbreak of COVID-19. But Pacific sailors still found their options drastically limited due to the islands’ sheer isolation.

The sailors I spoke to for this story, both on and off the record, noted that the nature of the Pacific crossing is about as ideal of a quarantine situation as a country could hope for.

“It takes 20 or 30 days to get here,” Andy Turpin said. “By the time you get here, if you’re not dead, you’re healthy!”

But he was equally insistent that sailors must abide by these restrictions out of respect for the government, and the local population.“We’re foreigners, and it’s a privilege to be in this country,” he said. “We need to respect that privilege, and be hyper-aware of how we’re perceived by the locals.”

Turpin was quick to point out that it was to the great credit of the French Polynesian government that sailors are allowed to stop at all — this spring, almost every port west of the islands had completely shut its borders. The ability to stop, provision, and make repairs, even if you’re required to quickly set sail again, is a life saver. And by most accounts, local shopkeepers and gendarmes, while taking restrictions seriously and exercising extreme caution, were still friendly, warm, and reasonably welcoming.

Of course, many Pacific sailors instinctively hoped to embrace the isolation offered by French Polynesia. Why not stock up, ship out, and go find yourself an abandoned atoll somewhere to ride out the pandemic?

But in addition to being foolhardy — it’s only so long before you run out of cooking oil, or water, or the like — Turpin argued that it was incredibly disrespectful to a country that had been hospitable to foreign sailors when it just as easily could have closed its borders.

“Don’t go off and try to be Robinson Crusoe! These atolls may be barely populated, but the people who do live there have cell phones, or satellite phones, and are able to communicate,” he said. “By doing that, you’re just making a point of your bad behavior, of your need to push limits. And there’s someone watching you, even if it looks like you’re in a dream. It belongs to somebody.”

This year, the stakes have been even higher. Sailors spend years preparing for a trip of this magnitude. They give up the creature comforts of land life in exchange for visions of roaming freely amidst halcyon waters. But in a pandemic, your plans and desires — as a sailor, an individual, and perhaps most significantly, an outsider — are quickly beside the point. The rude awakening facing these sailors as they made their way across the Pacific this spring was far more drastic than a tropical vacation cut short. It was an immediate referendum on what is, for many, a once-in-a-lifetime voyage.

“It has to all line up: your family, your house, your job. And, of course, preparing the boat and all the gear,” Turpin said. And there’s no easy way to backtrack under sail, he added. “If you blow past French Polynesia, blow all the way down to American Samoa, or the Marshall Islands, or Indonesia, you probably wouldn’t come back up here; it’s too hard a trip.”

He paused. “You’re probably only going to do this once.”

Verbena was one of those boats. This spring, after years of planning and preparation, the 55-foot yacht set out for a trans-Pacific jump. Verbena was home to seasoned sailors Bill Jacobsen and Renee Bushey, and their children Vera, 15, and Ben, 13. Based in Boston, they were in the second half of a year-long live-aboard sailing trip when Covid-19 hit. The parents had taken sabbaticals from their full-time jobs and the kids were adjusting to homeschool.

Renee and Bill spoke to me via Zoom in mid-April from Marina Taina in Tahiti — deeply tanned, wearing sunglasses, the sky blazed blue behind them. “Having this much family time was really the motivating factor,” Bushey said of their trip. “We get the kids for a year, and really get to spend time with them, rather than running to school, and sports, and so on.”

They purchased Verbena in February 2019, in Denmark, and moved aboard in July of the same year. After a round of boat maintenance and a short-distance trip to Copenhagen and back, the Jacobsen-Bushey’s officially started their trip on September 1, 2019. After a month of exploring the Canary Islands, they undertook their first major ocean passage as a family, crossing the Atlantic Ocean from Las Palmas to Saint Lucia in the Caribbean with a rally of other boats.

That Atlantic crossing, 16 days long, was not exactly smooth sailing. A technological glitch rendered their autopilot, which holds a boat’s course (and is a savior on long haul crossings) inoperable, forcing them to hand-steer for hours at a time.

As those exhausting days stretched on, Bill and Renee began asking themselves if they’d already had enough. Maybe they’d just go to the Caribbean. But after some time in Aruba, Bonair, and Curacao, “We just decided to keep going,” Jacobsen said. “We had sailed around the Atlantic before. We wanted to do the Pacific.”

Verbena set off for their Pacific crossing on February 27, 2020 from the Galapagos Islands in Ecuador with two crew members, David Kohn and Michael O’Brien, friends from Boston. They arrived at Hiva Oa, the easternmost island in the Marquesas archipelago, on March 12 after 15 and a half days at sea. The journey was the complete opposite of their Atlantic sail: a dream crossing. Verbena flew across the Pacific with 15 knots of wind behind the boat, making for a consistent, comfortable ride. Sunsets painted the sky fluorescent, night after night. They caught a 30-pound tuna. Conditions were smooth enough that the kids were able to do schoolwork, a near-impossibility on the choppy Atlantic crossing. Best yet, they found themselves with a regular escort of dolphins, a lively, smiling pod pacing the boat, leaping and playing in Verbena’s wake.

“I mean, we had dolphins, rainbows, everything!” Jacobsen recalled. “And we get to the Marquesas, and the world’s changed.”

Save the wild-eyed single-handers, sailing across an ocean involves a delicate balance of personalities. Tight quarters, tenuous conditions, and usually, a marked lack of sleep can quickly heighten tensions and shorten fuses. A family aboard is not uncommon, but many Pacific crossers are solo sailors who attach themselves to a boat and captain, putting in the work to earn a place, and a passage, without necessarily having a great deal of say in where that boat will go, and what longer-term travel plans may be.

Karine Marois, 28, is one such sailor. She grew up sailing under the tutelage of her father, who completed his own Pacific crossing 30 years ago. Eager to follow in his footsteps, she gained experience racing sailboats in Newport Beach, California, all while dreaming of the open ocean.

After eight years of planning and four of saving funds as a quality assurance coordinator for a vitamin supplement manufacturer, Marois was ready to make it happen. She advertised her interest and availability via sailing magazine Latitude 38’s crew list, and participated in the Baja Ha-Ha, an annual rally from San Diego to Cabo San Lucas. She found a place aboard a 42-foot catamaran (whose captain preferred to remain anonymous). On February 18, they embarked on their crossing, arriving in the Marquesas 32 days later. Over the course of their month-plus at sea, Marois and the crew realized that the situation on land would likely be very different than they had anticipated.

Communication capabilities vary by boat. A satellite connection might permit for some at-sea internet access. A two-way radio allows you to connect with other boats, people on land, and occasionally, aircraft, but its capabilities (and clarity) depend on distance. Aboard the Verbena, the Jacobsen-Busheys infrequently checked email and downloaded weather reports via satellite; news of the pandemic largely hit them upon their arrival in Hiva Oa. Marois, by contrast, used a handheld satellite device to share her location and correspond with friends and family via 160-character messages. Starting around March 8, the pandemic dominated those messages — job losses, shutdowns, and cancellations of major events, like ComicCon and Coachella.

Marois and her shipmates discussed the developments every morning, increasingly unsure if they would be able to enter the country at all. On March 19, an official announcement from the French Polynesian government proclaimed a moratorium on all boat movement, effective March 22; Marois and her shipmates arrived in Nuku Hiva just under the wire, on March 21.

Verbena arrived a week prior to the lockdown order At first, restrictions were limited to cruise ships, which either returned to their home ports or repatriated their passengers through the capital city, Papeete, on April 11.

“At first, I thought, ‘Wow, we’re lucky,’” Bushey said. “We’re out in the middle of nowhere, with hundreds of islands in the vicinity; if we have to spend a few more weeks cruising around here, great.” Their crewmates, Michael O’Brien and David Kohn, quickly realized that they needed to move quickly if they wanted to get back to Boston. Kohn flew back to Boston on March 17 — three days before his previously booked flight, scheduled for March 20, which was eventually cancelled.

“I could have been stuck there, unwittingly, for much longer,” he said, back home in Boston a month later.

So much of life comes down to timing, and sailing is no exception. Leave for a passage a few days late or early, and you might encounter too much wind, or not enough. You could skirt a countercurrent threatening to push you backwards. You could spend days floating in glassy doldrum seas, upending any predictions you might have had about the number of days you’ll spend at sea, and the number of days until you see land again.

The power of timing hit sailors even harder during the pandemic. David Kohn, aboard Verbena, managed to squeeze through a narrow window of opportunity to make it home to the United States. For Paul Hofer, the time crunch presented far more significant challenges.

Hofer, 57, is an avid sailor, originally from Kansas and now based in Los Angeles. He was crossing the Pacific aboard Serendipity 2, a 50-foot single-masted sailboat when the crew received word via satellite that French Polynesia was shutting down all inter-island travel and severely restricting sailors’ movements. Boats were limited to one trip to shore per week, with just one crewmember at a time, and required to submit new forms at the dinghy dock. All islanders and sailors were prohibited from entering the water, for recreation or bottom cleaning, which boats typically require after long crossings when algae and other growth accumulate. Boats were not allowed to visit each other, a nightly curfew instated, and alcohol sales suspended.

While Hofer was inclined to divert up to Cabo San Lucas or even back to Los Angeles, the captain disagreed. As they sailed on, Hofer immediately began to strategize an exit strategy. Over a handheld satellite device with a broken charging port, he messaged his wife, Gena: “GET ME HOME!”

Gena Hofer, 56, immediately began charting the best route to get Paul from the Marquesas to Tahiti, and from Tahiti to the U.S. The final flight from Tahiti to the U.S. this spring, landing in San Francisco, would leave the evening of March 28; it was impossible for Serendipity to cover the additional 900 miles to Tahiti by then. Gena hitched her last hope to somehow chartering a flight from Nuku Hiva to Tahiti in time to catch that March 28 flight.

“I exhausted every option,” Gena said. “I booked so many tickets for him. I sent emails to the American Citizens Services, and to the U.S. Consulate. I contacted the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program.”

Finally, she got through to an agent at the U.S. Embassy in Papeete, who helped them arrange a $40,000 charter flight from Nuku Hiva. Nineteen other cruisers opted in, along with seven locals from Nuku Hiva who required non-COVID-related medical care. The three days between Paul’s arrival at Nuku Hiva and departure were filled with uncertainty and stress — would they get enough sailors on board to make it feasible? How would they get to shore, and to the airport on the other side of the island, when land access was so limited, and on-island travel strictly forbidden? When they did, would the plane even show up?

On the morning of March 28, Paul Hofer and the 19 others shuttled to shore, where they were met by a group of gendarmes and loaded into a convoy of taxis. The group snaked up the mountain along a winding, vertiginous road. In spite of the tension, the drive was breathtaking — a dense canopy of rainforest rising steeply from the crescent moon-shaped harbor below, dotted with the stranded fleet.

The flight arrived and departed on time. Hofer, after days on pins and needles, overwhelmed with worry that he wouldn’t make it home, could finally breathe. “It’s hard to believe that it happened, hard to believe that I’m not still sitting there in Nuku Hiva,” Hofer said, as he and Gena spoke to me from their home in Los Angeles. “It’s amazing that she pulled this off.”

But unlike Hofer, a majority of sailors who found themselves in Nuku Hiva at the end of March, including Andy Turpin, Karine Marois, and the Jacobsen-Busheys, decided to stay. Turpin, in contrast, actually flew back to French Polynesia on March 17 from San Francisco; he and his wife, Julie, had sailed to Nuku Hiva from Tahiti in January, “an 800-mile windward slog,” and returned to California for business and family reasons.

“If I hadn’t been able to get here, I would just be tossing and turning wondering if my boat was up on a reef, or something!” he said.

On the other hand, Karine Marois worried she could be forced to leave French Polynesia and return home to Southern California. Her goal for this trip was to spend the better part of a year sailing, eventually landing in Australia, where she had lined up a work visa.

“I did not want to be put on a plane to be repatriated back home,” she said. “I’m scared of being forced to end this whole adventure I had planned and saved for only halfway through.”

But staying comes with questions of accountability. If something were to go wrong, what is the sailor’s place among the local population?

The Jacobsen-Busheys, for example, quickly confronted the confinement of living in anchorage. Sitting at anchor with no land access is difficult enough; not being able to jump in the water is a quick recipe for cabin fever. “It felt like a lot of people were watching their neighbors,” Renee Bushey said.

Karine Marois felt similarly confined by the restrictions but felt strongly that solidarity with the local population was, and is essential for the cruising population.

“If locals aren't allowed to go for a swim, they don't want to look out at the boaties out there splashing around!” she said. “We’re all trying to be good, and to respect laws put in place. We don’t want them to get sick of us and say, ‘You’re on their own,’ because they’d be well within their rights.”

Sailing can appeal to lone wolves, those who want to disconnect and escape the pressures of society. And while that holds on the open ocean, sailors at anchor are unbeatable when it comes to forming instant, tight-knit communities. Sailors share stories, swap spare parts and speak a common language; if you’re proficient, you’re immediately welcomed into the fold.

Karine Marois experienced this warmth upon her arrival in Nuku Hiva, when a pair of cruisers in a dinghy greeted her boat with a basket of fresh fruit and vegetables — pure gold for a cruiser off a long passage fueled by mostly repetitive meals of canned and dried goods. Since local gendarmes prohibited the boats from boarding each other's vessels — ordering any attempted boarders to cease and desist, via loudspeaker —the harbor’s nearly 100 stranded boats found other ways to support each other. They set up a multitude of “nets,” or radio networks, including daily updates on travel restrictions, a French-language hour, kid’s programming, and nightly trivia. The net was also how Marois found passage to Tahiti.

After putting out a call to the fleet, she found space aboard Aurora, a 43-foot cutter-rigged sailboat that brought her to a new, temporary home in Tahiti’s Papeete Marina. Photos from her time in Papeete showed her tanned and smiling, dressed in shades of blue, often with a slick of bright blue lipstick, posing with the hull of Aurora, or in front of the colorful street art around the city on her provisioning runs.

The cruising community was strong there, too, she said.

“It’s one of the high points of being in a marina, versus an anchorage — we get to have face-to-face interactions!” Marois said. “But I want to stress that we are socially distancing.”

She settled into something of a routine. Two women from other boats led exercise classes every morning at 7 a.m., alternating between yoga and a high intensity workout. She and the crew of the Aurora tried to get one productive thing done before midday, when it got too hot for boatwork. Then, a cold water shower — “Which is so, so nice!” — followed by a trip to the store. In the evening, the younger sailors of the ARC rally gathered for a socially distant happy hour. Then dinner and a movie with her shipmates from the teradrive of science fiction and Disney films she brought aboard. Those were doses of stability in a fraught year of global turmoil.

Sailing-centric Facebook groups abound, including one dedicated to cruisers in French Polynesia, with 1,800-plus members. This spring, most posts tracked changing regulations, or offered tips and support for stranded cruisers. But there was still the occasional boundary-pusher — someone seeking information about entry to an isolated atoll, antsy and impatient for respite from stagnant limbo. They were usually reprimanded by other group members, but the tension was palpable.

“The whole bedrock of this tight knit cruiser community centers on coming and going when you want. You know you’ve got to make the most of those bonds when you're here,” Bill Jacobsen said. “That’s all been shaken. No one wants to live like this for three months. Most of us choose to be on the move. If you can’t be, what’s the point?”

Not all storytellers are sailors, but all sailors are storytellers. And there is no shortage of stories — of upended crossings and the heartbreak of cancelled trips — to tell this year.

Underneath them all is a story whose ending is yet to be written, but still plagues the minds of travelers around the globe: What will the world look like when this is all over? Will we ever be able to explore new places with the same freedom?

Andy Turpin has spent the last 23 years encouraging sailors to explore the South Pacific and has spent a great deal of time in the region himself. But when we spoke this spring, he was the first to say this was absolutely not the time to make the crossing.

“I understand that, after years of preparation, it’s heartbreaking to hear, ‘Don’t go.’ But if you do get here, and you’re not able to go to the inner islands, and you’re just stuck in this harbor… what’s the point?” he said. “Plus, to force the issue and barge in now… why would you push that?”

The added stress of COVID-19 and governmental lockdowns tested the relationship between cruisers and locals, which had already shown signs of strain, especially as the number of cruisers in South Pacific waters has steadily increased.

“And it only takes one or two people to screw things up,” he acknowledged. “That said, on the scorecard, I think we’re doing pretty good. And [following safety precautions] is not just out of self-interest… it’s the right thing to do.”

Kevin Ellis, an American expat, runs Nuku Hiva Yacht Services with his wife, Annabella. Together, they help sailors sort through official formalities, acquire parts, make repairs, and more. This spring he became the primary liaison between the cruisers in Nuku Hiva and the local government. Ellis thought that it was inevitable that dynamics would change, not just in French Polynesia, but everywhere.

“I am sure that everyone in the world is looking at people they don’t know differently than they did before, with more fear of the unknown,” he said.

For the family aboard Verbena, 2020 was always going to function as a year-long sabbatical. The pandemic drastically disrupted their route, but it hadn’t changed their timeline. If anything, their sojourn has prepared them for a return to landlocked COVID-reality — their kids had been homeschooling since the fall, and the family was already used to being separated from their friends.

As they tried to remain clear-headed, they couldn’t help but mourn their original vision for the crossing.

“I had in my head that this would be the last long offshore sailing. Our last long passage! We were just going to hop island to island,” Bushey recalled. The reality of their voyage was crushing, she said. “I’ve slowly come to terms with it. Not least because we’re seeing all the other problems in the world. Life is long, and hopefully we can do it another time.”

By late April, restrictions in French Polynesia began to loosen. Shops, restaurants, food trucks, and beaches reopened, as did the waters for swimming and recreational activities.

“What can I say? We sailed over 10,000 miles to get here,” Jacobsen said. “There’s no way to extract the COVID-19 experience from our South Pacific experience.” Ben, his son, comes into view and waves hello; he’s just finished his Latin homework and heads below deck.

“I was talking to my daughter, Vera, the other day about our situation. And she said, ‘If the world goes to hell, at least I know how to sail!’”

Months have passed since I first connected with these sailors and, of course, a great deal has changed in the meantime. Covid-19 continues to dominate the headlines, and our lives, as cases skyrocket around the world.

After reopening borders to tourism and lifting quarantine requirements in July, French Polynesia has seen its own Covid-19 surge. As of mid-November, the country reported more than 11,000 cases and 52 deaths. Sailing westward to other countries is now possible, but it is still incredibly difficult, and far from a sure thing. Tensions between sailors and locals have continued to mount. Olivier Meurzec of AVP said that friction has been building for years due to the increased number of sailors coming to French Polynesia, many for multiple seasons at a stretch. Despite the growing number of arrivals, infrastructure in marinas and anchorages has not been able to keep up, leading to overcrowding throughout the archipelago.

“In many locations, threats, insults, and outright attacks have taken place, almost daily,” Murzec wrote in an email in May “Mayors have issued decrees prohibiting boats to anchor. [Covid] has had another negative impact on mentalities, reminding the local people of the germs and viruses brought by foreigners landing on the shores of French Polynesia in the 19th century, almost wiping out the Marquesian population, and decimating the other isles.”

As for our Pacific sailors? Andy Turpin is still in French Polynesia, along with his wife, Julie, who eventually joined him there. Paul Hofer is with his boat, Scarlet Fever, in Marina Del Rey, California, and is hoping to embark on a two- to three-month cruise to Barra Navidad in Mexico at the end of the year, assuming he feels safe doing so.

The Jacobsen-Bushey’s shipped Verbena back to Wilmington, North Carolina on August 11, and flew back to the U.S. the same day. They spent the summer sailing around the Tuamotus and Society Islands — diving, hiking, fishing, and spending time with other families they had befriended during their travels. In late September, they sold Verbena before she was unloaded from the transport ship to a new owner planning a long-haul ocean journey of his own.

And Karine Marois, through much persistence and no small amount of hope, is still sailing. As I write, she is en route to New Zealand, crossing from Fiji, aboard a catamaran called Kefi. Since we first spoke in the spring, she applied for permission to enter Australia four times, and New Zealand twice; in late October, she was designated as essential crew, earning her a visa. She also made it to Musket Cove Yacht Club, where she found a record of her father’s boat, which she’s since tracked down in Australia.

“It's stressful at times not knowing what'll come next, and frustrating to have to surmount obstacles which never even existed before,” she said. “Overall, I keep thanking my lucky stars given how the rest of the world is doing with this ongoing crisis.”

She’s right — the upending of her personal plans aside, Marois is far better off than much of the world. And these stories of sailors, stranded just off of paradise, are not the most pressing in a year full of bleak and relentless breaking news. Countries are shut down, once again. Economic crises seem to multiple by the day. A fraught election has led many to a bipartisan agreement that our very democracy is on shaky ground. And still, an invisible enemy is ravaging our world, leaving marginalized communities to bear the most devastating brunt. Upended sailing trips are not the stuff of life or death.

But the sailor, and the storyteller, in me wants to tell it nonetheless. I want dream trips to come to fruition — if not this year, then next, or the one after that. I want journeying on the vastest scale to be proven possible. Because what a world! To be able to cast off, raise the main, set a course, harness the wind and cross an ocean. I want, I need, to believe in a world that’s ours for exploring again.

TIP JAR💰

Loved this issue of We’ll Have To Pass? Then Venmo the author, Lauren Sloss $5 directly @lauren-sloss. To support her other amazing work, follow her on Twitter @laurensloss.

This issue of We’ll Have to Pass was edited by Eleanor Cummins, Sarah Cummins, and Marion Renault. Our logo design is by Mariana Pelaez.

For just $5/month, you can help us publish incredible stories that otherwise may never have existed.